Designer: Design firm of David Kleinberg, more details below.

By Carl J. Dellatore

In my book “Interior Design Master Class,” legendary American designer David Kleinberg wrote, “To define taste as an aesthetic idea is like trying to describe the color of oxygen. It is ephemeral in every sense, personal in every way and subject to the vagaries of society and fashion, yet it is a constant we somehow recognize, like perfect pitch.”

Of course, Kleinberg was correct in his assessment: Defining good taste is challenging, as it is inherently subjective and varies widely across cultures, eras and individual experiences. What one person considers elegant or stylish, another might find unappealing. This subjectivity arises from the complex interplay of personal preferences, cultural influences and life experiences, making it unique to each individual.

Good taste is often confused with specific standards, levels of sophistication or refinement, but these standards are not universal. Cultural norms, social expectations and economic factors shape them. In practical terms, for example, a minimalist design with clean lines and a neutral palette might epitomize good taste in one context. At the same time, a richly decorated, maximalist interior might be prized for its vibrancy and character in another.

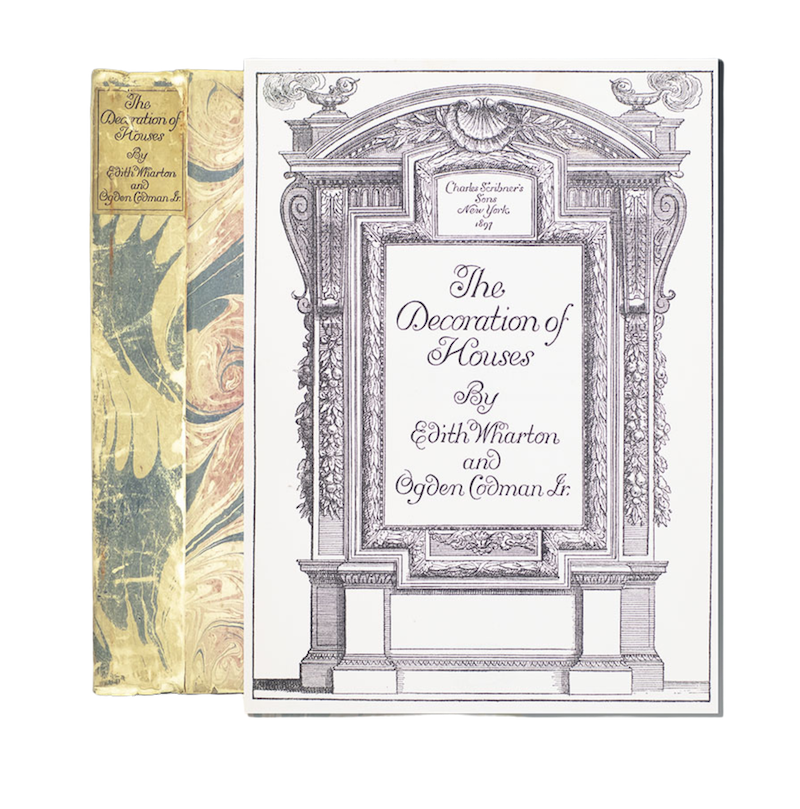

In “The Decoration of Houses” (1897), which defined the interior design profession, authors Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman Jr. emphasized that good taste in interior design is rooted in simplicity, harmony and respect for architectural integrity. Wharton argued that authentic good taste avoids excessive ornamentation and favors restraint, exacting attention to proportion and carefully selecting quality materials. In reaction to the Victorian era, she criticized blindly following fashion or indulging in overly ornate decorations, which she believed compromised a space’s elegance and functionality.

Wharton also highlighted the importance of understanding a home’s historical and geographical context, suggesting that interiors should complement the building’s structure, location and purpose. For Wharton, good taste was not about following rigid rules but about cultivating an eye for balance, unity and enduring qualities that make a beautiful, livable space.

Today, good taste is often confused with extravagance or the perception of luxury, but authentic good taste transcends hefty price tags and shiny surfaces; it is deeply intertwined with what suits one’s lifestyle and brings well-being. In this sense, good taste becomes a personalized concept, where the beauty of a space lies not only in its visual appeal but also in its ability to cater to its inhabitants’ unique needs and preferences.

As a designer, you know taste is fluid and can evolve as you mature in your career. Furthermore, the rooms clients appreciate or consider tasteful in their youth might change as they age and their life circumstances shift. This fluidity further complicates defining good taste in absolute terms.

But for me, there is one constant in beautifully designed rooms: comfort.

It is the final and arguably most important element of good taste. No matter how beautiful a space may be, if it is uncomfortable, it fails to serve. Comfort can be physical, like the feel of a plush sofa, or emotional, like the warmth evoked by personal mementos displayed around the home. When a space is designed with comfort in mind, it invites relaxation and ease, making it a perfect backdrop for the business of daily life.

Stay updated on this series author, Carl Dellatore, by following his Instagram. About Carl Dellatore & Associates – provides designers, architects, and creatives with writing, editing, and copyediting services by an established team to effectively reveal your story.