Designer: Juan Montoya; more details below.

By Carl J. Dellatore

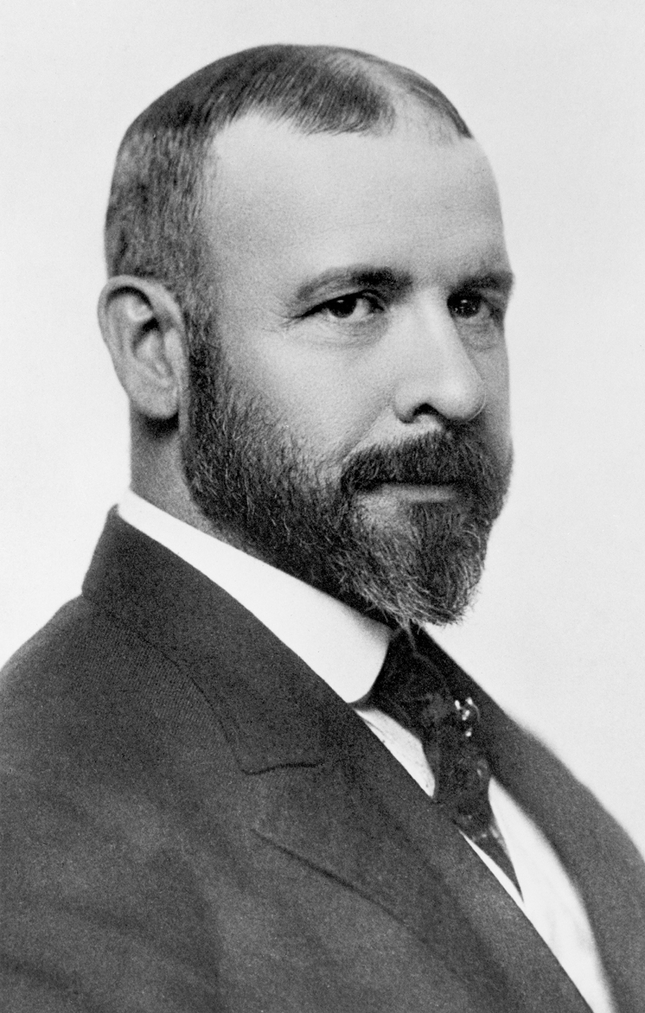

I would argue that Louis Sullivan’s ideas influence interior design as we know it today. But I’m ahead of myself. Let me explain.

You likely know Sullivan’s work. He is hailed as the “father of modern architecture,” leaving an indelible mark on the design and construction world and influencing architects and designers today. His innovative ideas and groundbreaking contributions reshaped American cities’ skyline and laid the foundation for modern architectural principles.

Born on September 3, 1856, in Boston, Massachusetts, Louis Sullivan displayed a remarkable aptitude for drawing and design from a very young age. His early exposure to architecture and art laid the groundwork for his future accomplishments. His journey into architecture began with formal training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he honed his skills and absorbed architectural traditions.

Sullivan’s breakthrough came when he joined forces with Dankmar Adler, a renowned structural engineer, to form the architectural firm Adler & Sullivan in 1883. This partnership would be a turning point in his career, leading to numerous groundbreaking projects and innovations.

But Sullivan’s most significant contribution to architecture was developing the “form follows function” principle, which emphasized that the design of a building should be dictated by its purpose and function rather than being purely ornamental. Sullivan argued that architecture should be honest, reflecting a structure’s inner workings and purpose. This revolutionary idea laid the foundation for modernist architecture and influenced architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Marion Mahony Griffin, and Thomas Tallmadge.

The application of the form follows function principle is most notable in his design of the first skyscrapers. During the late 19th century, as American cities were proliferating, there was a need for taller buildings to maximize limited urban space. Sullivan’s innovative approach to skyscraper design included a steel skeleton structure, allowing for taller and more efficient buildings. His Wainwright Building (built to house the Saint Louis Brewers Association) was completed in 1891; it is a prime example of this approach. The building’s exterior reflects its internal organization.

Sullivan’s influence extended beyond individual buildings and the development of the modern skyscraper. He wrote extensively on architectural theory and practice, sharing his ideas and philosophies with the world. His book, “A System of Architectural Ornament,” remains a valuable resource for architects and designers, providing insight into his artistic vision. (Sadly, the book is out of print, though it is readily available in PDF form online.)

Sullivan’s emphasis on functionality extended to furniture design. He believed furniture should be designed with the user’s needs in mind. This view coincided with the shift in furniture design in post-Victorian America and marked a significant departure from the ornate and heavily embellished styles of the time.

Speaking about the shift away from the Victorian era, I’d be remiss if I didn’t remark on Edith Wharton and Odgen Codman’s groundbreaking book, “The Decoration of Houses.” Though there is no documentation I could find on Wharton being influenced by Sullivan, it is easy to imagine how Sullivan’s views informed Wharton and Codman’s perspective on post-Guilded Age rooms.

Years later, the Arts and Crafts movement originated in England but found a strong following in America and was pivotal in shaping post-Victorian furniture design. Advocates of this movement, such as Gustav Stickley, believed in the value of handcrafted, well-made furniture. They embraced natural materials, simple lines, and an emphasis on the inherent beauty of wood grains. Mission-style furniture, characterized by its clean lines and geometric forms, became a hallmark of this movement.

The shift in furniture design also aligned with broader societal changes, and the early 20th century brought about industrialization and urbanization, which led to smaller living spaces. As a result, furniture needed to be more compact and efficient. Designers like Frank Lloyd Wright (once an underling at Sullivan’s architecture firm) began creating furniture that was not only aesthetically pleasing but also practical for modern living.

Mass production revolutionized furniture design in the 1940s and 1950s, defining an era that emphasized accessibility, functionality, and sleek details. During this period, midcentury modern design arrived, celebrating clean lines and organic shapes.

Furniture designers like Charles and Ray Eames, Eero Saarinen, and George Nelson embraced mass production methods, particularly molded plywood and fiberglass. These techniques enabled the efficient creation of iconic pieces such as the Eames Lounge Chair and the Tulip Table. Assembly manufacturing made these designs affordable and readily available, democratizing access to stylish, well-crafted furniture. It is easy to see how these designers put the function of their pieces at the conceptual forefront–to my mind, a nod to Louis Sullivan.

In the 21st century, Sullivan’s principles resonate strongly in sustainable architecture, where functionality and environmental considerations have become paramount. Contemporary interior designers continue to be influenced, too, evidenced by how designers organize floor plans to respond to activities and tasks and how furnishings are tailored for suitability and comfort.

While Sullivan died in 1924, nearly a century ago, his legacy reminds us that three simple words, form follows function, continue to shape architecture and design, facilitating and enriching our modern lives.

Stay updated on this series author, Carl Dellatore, by following his Instagram. About Carl Dellatore & Associates – provides designers, architects, and creatives with writing, editing, and copyediting services by an established team to effectively reveal your story.